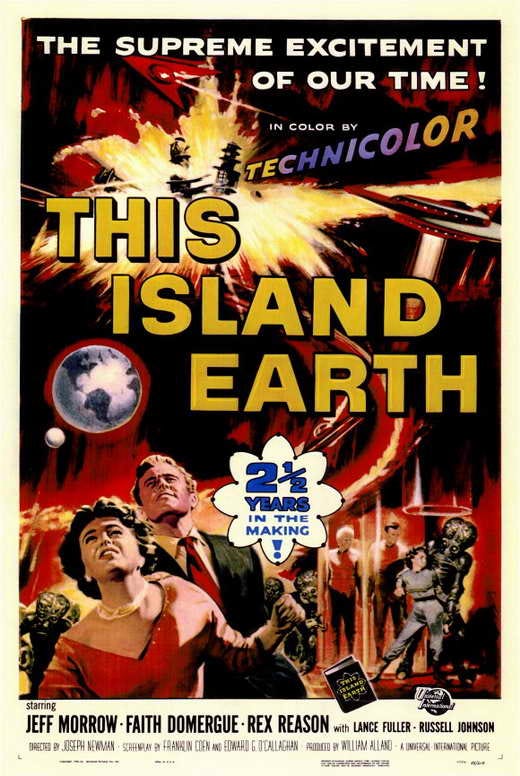

This Island Earth (1955)

“We’re not all masters of our souls.”

A series of puzzling events leads electronics and nuclear science researcher Dr. Cal Meacham to “The Club” - a highly advanced research facility run by the mysterious Exeter. Although Exeter claims to be working towards world peace, other researchers there seem ill at ease. Cal and fellow scientists Ruth Adams and Steve Carlson begin to put the pieces of the puzzle together, but even their brilliant minds cannot conceive that the survival of a civilization hangs in the balance.

Summer films need to be lean, and at eighty-six minutes in length, This Island Earth doesn’t have an ounce of fat. Each moment of action seamlessly connects with a puzzle to spark the viewer’s curiosity and pull them forward. While director Joseph M. Newman obviously deserves a great deal of credit for this, he was also lucky enough to be working with editor Virgil W. Vogel, who was on the cusp of making his own jump into a long and successful career as a director. As well, in one of the very few cases when this seems to have been successful, the studio ordered an entire section of the movie to be reshot with a different director. All the scenes on Metaluna were directed by Creature from the Black Lagoon’s Jack Arnold, and it’s hard to argue with their choice for a pinch hitter.

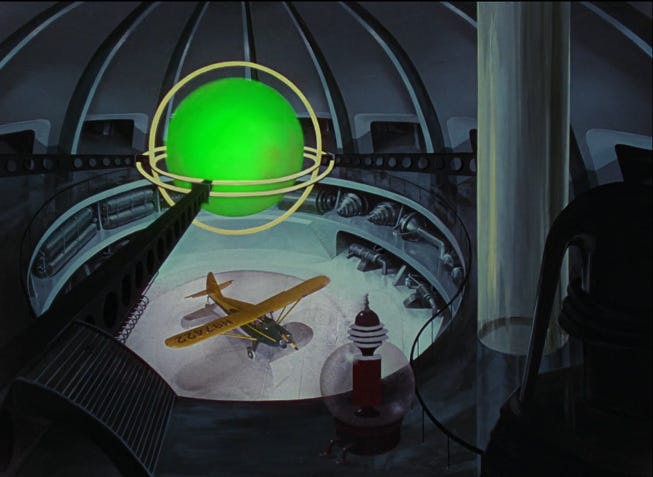

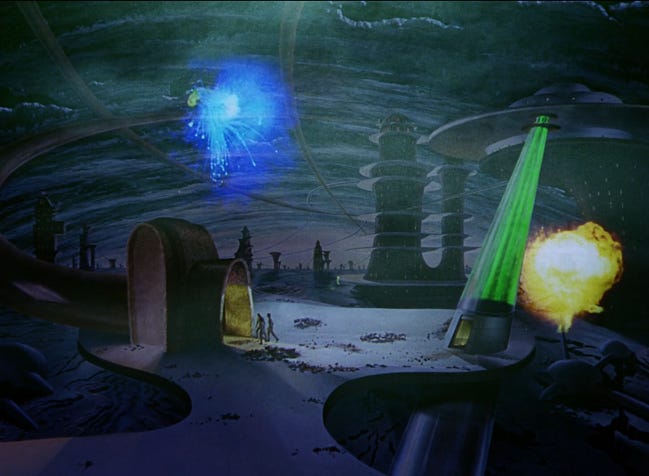

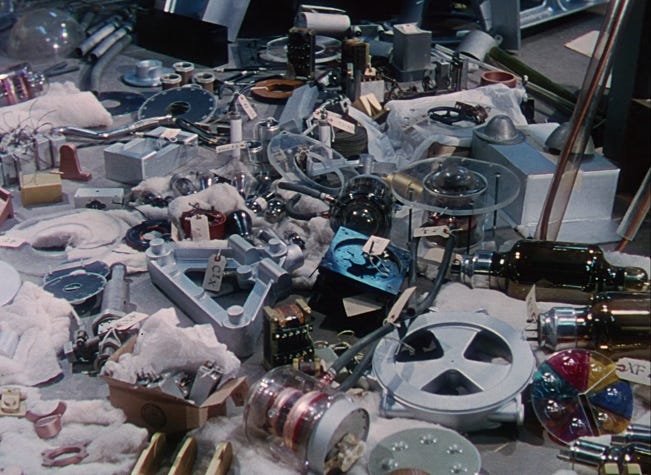

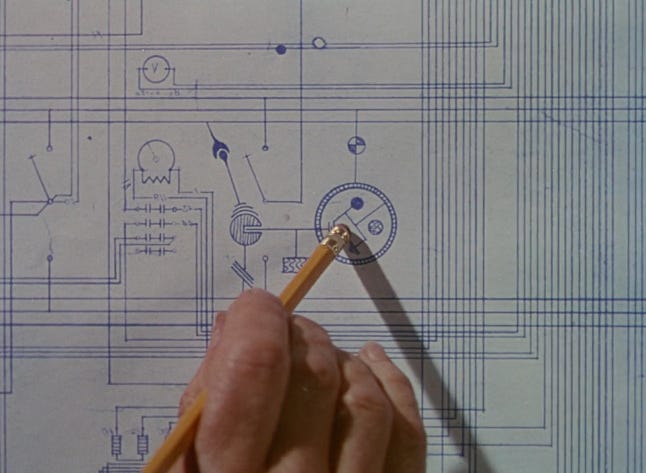

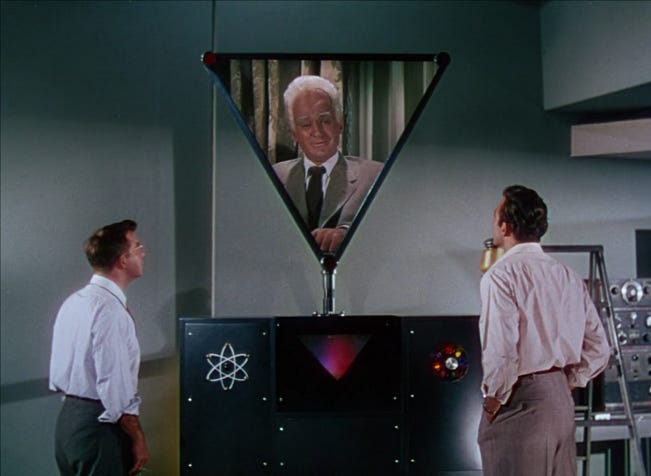

This first thing that strikes one about This Island Earth is the incredibly vibrant color. As of 1954, over 50% of American films were in color, but this was Universal-International’s first color science fiction film. The three-strip Technicolor is stunning, allowing cinematographer Clifford Stine to capitalize on elaborate sets and the efforts of a first-rate special effects team. The Club (especially Exeter’s office and the lounge) is a model of opulence, and the surrounding countryside is also breathtaking, but the movie excels where it takes made-up science by the horns. The labs are agog with dials, meters, levers and tubes, and the montage of the construction of the Interocitor communication device is a delight. The control interfaces on the Interocitors and in the spaceship are fabulously unlikely, but also a reminder of the surprising persistence of mechanical controls in science fiction. We would, in fact, still have to wait twenty years for the idea of touch screens to arrive. The Metalunans’ oversized heads encased in clear plastic helmets and the fabulous pincered — yet inexplicably bespectacled — Mutants add to the film’s delightfully retro look. Many shots are also surprisingly complex. I was frankly astonished at the expert use of matte paintings as well as the unusually dynamic attacks of the Zagon ships. The Metalunan spacecraft’s descent through the battered surface of the planet to the refuge below is one of the most imaginative and stunning sequences in mid-20th century science fiction, reminding us that the effects team were veterans of classics such as Frankenstein (1931), King Kong (1933), The Invisible Man (1933) Frankenstein, and It Came from Outer Space (1953). The visual effects in This Island Earth are not only top notch, but in many respects ahead of their time.

As with many early science fiction films, the anachronistic quality of its failed scientific predictions is fascinating. The idea that leaving a planet’s orbit would necessitate going through some sort of “thermal barrier” might have been plausible in 1955, as could the concept of a conversion process allowing humans to survive in environments with high levels of atmospheric pressure. Even at the time, however, devices which bind your hands to metal rails with magnetism or ionization shields to produce planetary shields were pure fancy. Some of This Island Earth’s speculations survive in science fiction to the present day. Star Trek is rife with references to a “Galactic” or “Great Barrier” surrounding the Milky Way. The idea of bombarding a planet with towed meteorites, as the Zagon ships do with Metaluna - is a plot device I remember recently being convincingly used in The Expanse.

There is, however, also much to puzzle over, and This Island Earth fails to reach its full potential in important respects.

Skilled actors, working with a sound script and guided by a talented director, can accomplish incredible things. These three elements are especially important in the case of science fiction, where the fantastical underpinnings of the stories can make it much more difficult for the audience to suspend disbelief.

Most of the characters in This Island Earth are, regrettably, one dimensional. Cal Meacham (played by Rex Reason) is at the zenith of his career. Possessing a voice of ungodly masculinity and a maverick spirit, he has a single direction (forward), a single mode (absurdly confident), and is so vital to the nation that the Army has lent him a jet for his personal use. Dr. Ruth Adams (Faith Domergue) and Dr. Steve Carlson (played by Gilligan’s Island’s Russell Johnson), for their part, spend the first half of the movie with terrible cases of “resting conspirator face,” sharing so many dark and brooding glances that even the cutlery knows something is brewing. Once they leave Earth, it suffices for Domergue to place herself in situations of maximum peril and scream until she is saved by Cal.

On the surface, this could seem like bad acting, but what seems like bad acting isn’t always the actor’s fault.

One problem is that the actors are asked to do the impossible. The most obvious example is when Cal and his assistant Joe Wilson (played by Robert Nichols) first see Exeter (Jeff Morrow) and his enormous head in the lab. Okay, I can see that, being of superior breeding and tact, you don’t draw attention to it when you’re talking to him directly. But you can’t tell me the first thing you do after the Zoom call ends isn’t to turn to your each other and say, “Did you actually see that guy’s head?!” By the time Cal gets to The Club and sees more of them walking around it becomes heroically implausible to think that Cal, Ruth, Steve, do not realize that these are guys from space. I can see the actors not objecting when reading the script, but there must have been a minor mutiny when they saw the prosthetics that were being used. While I can’t say Reason, Domergue and Johnson are great actors, I can admire their exquisite ability to stay in character when reading lines like:

Ruth: Do you notice the peculiar indentations in both their foreheads?

Cal: Coincidental, no doubt.

A crucial failing in This Island Earth is that it either avoids or gives short shrift to anything that could have made it actually about something. The Cold War was running quite hot in the first half of the 1950s. The Korean War ended inconclusively in 1953, the First Indochina War ended in 1954 with a communist victory, and the Warsaw Pact came into being in May 1955. The idea that freedom and democracy was in an existential struggle against communism was regarded as scripture. McCarthyism, in its heyday from 1950-1954, directly challenged the sanctity of individual liberties in the face of the communist threat. Some films, most notably 1951’s The Day the Earth Stood Still, directly confront not only the absurdity of our collective paranoia, but the mortal danger our delusion of control puts us in. Klaatu’s exasperation at the American government’s Cold War mentality of intransigence becomes our own, and his disappointment at how easily the press is able to manipulate public opinion prompts us to reflect on our inability to evolve as a species. Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) is also a brilliant reflection on both the Red Scare and fears of life under Communist rule.

Try as I might to find parallels in the script of This Island Earth to the geopolitical realities of the time, I draw a complete blank. The film is also saddled with a generally lax attitude towards explaining anything about the situation on Earth or beyond. Neither the university nor the government are interested enough in the incredibly advanced technologies that Cal has become privy to provide him with backup. Even more strangely, the Metalunans do not seem to understand why they are at war with the Zagon.

I mentioned the actors being asked to do the impossible, but equally strange is the fact that they are asked to do so little. An exploration of the ethical issues implicit in This Island Earth could have added real depth to the story. Though they are faced with imminent extermination at the hands of the Zagon, the Metalunans ultimately kill scores, quite possibly hundreds, of humans without hesitation, and they are prepared to subjugate the Earth itself if humanity won’t accept their rule. Does the end of species survival justify the means? Cal, for his part, seems somewhat put out by the loss of life - but he’s apparently polite enough not to belabor the point. Exeter, although he finally saves Cal and Ruth from not only the mind-control procedure but also from the destruction that ultimately engulfs his planet, appears to do nothing to try to alter the course his fellow Metalunans have embarked on. His arguments against using mind control are merely instrumental - the techniques are not necessarily evil in themselves, they just don’t produce the results they want. And despite knowing the Metalunan plan to take over the Earth, Exeter only asks Cal and Ruth not to judge them too harshly.

When lives or freedom are at stake I want to see more. I want to see characters denouncing evil with clenched fists raised in the air. I want to see passionate arguments for the right and the good. Rather than saving Cal and Ruth behind the Monitor’s back in the last moments of the film, Exeter should be striving desperately to save both his civilization and humanity, even if his efforts ultimately fail. The fate of worlds should rest on the decisions that the characters make. In contrast, once Cal steps inside the plane to go to The Club, and especially after he and Ruth leave Earth, we’re basically riding The Pirates of the Caribbean at Disneyland - every action seems predetermined. In fact, for all the visual splendor, once the characters arrive on Metaluna the planet has less than an hour until its destruction. Earth is saved, but it’s not because of anything that anyone does. The fates of both Metaluna and Earth are decided even before the film begins.

Narratively, this is failure upon failure, and no amount of competent acting could have remedied the script’s shortcomings. Had Franklin Coen imbued the story of This Island Earth with some depth of characterization, had he sunk his teeth into the thornier and more meaningful aspects of the story, it could have transcended the level of light entertainment. As it is the film has nothing to teach us, and it certainly doesn’t prompt us to reflect our own attitudes or the values of our society.

But, let’s be honest, sometimes being entertained is enough. Two of the most important action-adventures of all time - Raiders of the Lost Ark and Jurassic Park - are rife with plot holes, continuity problems, and a lack of character development, yet they are also regarded as nearly perfect movies. One reason why is because they stay in their lane. What counts in a summer popcorn movie is the sense of wonder, the thrill of the chase, and the ultimate triumph of good over evil. This Island Earth checks all three boxes easily. Yes, it is far from a perfect movie - but it is perfectly good, and visually spectacular, summer fare.