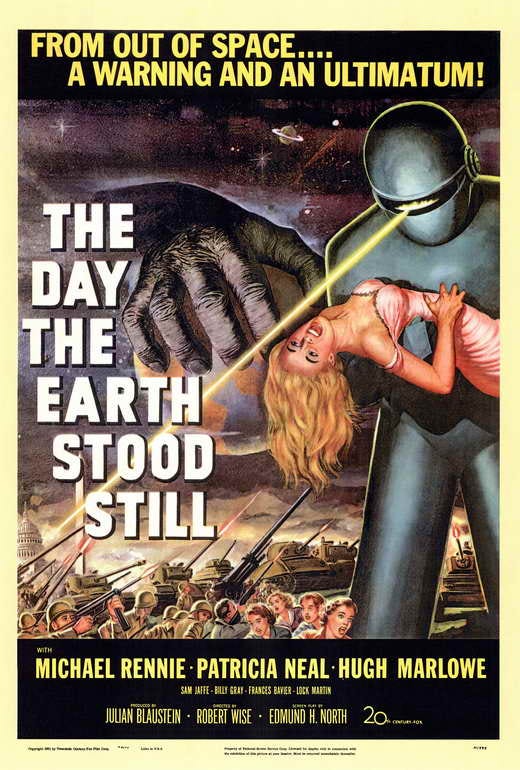

The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951)

“Then the milkman screamed and pointed up at the sky.” - Donald Fagan, Tomorrow’s Girls

A spacecraft lands in Washington D.C. and its two occupants emerge. One, Gort, is a giant robot of incredible power, while the other, Klaatu, has a completely human appearance. Things quickly go awry, and a soldier’s nervous trigger finger leads to Klaatu being injured. A representative of the President is quickly dispatched to meet with Klaatu, who tells him that he has a message of dire import for the nations of the world. When his efforts to convince the White House to organize a meeting of the world’s leaders fail, Klaatu escapes to try to find a way to convey his message. A frantic search for the spaceman is initiated, leading to rising panic. Meanwhile, Klaatu learns about the Earth and its people, but his patience is running out, which could have terrifying consequences for all.

While it’s undoubtedly true that many great films give us insight into who we are, equally valuable, perhaps, are films that help us understand when and where we are, and where we might be heading. Science fiction movies which comment on social or political themes are hardly unusual nowadays, but before The Matrix, Avatar, and They Live there was The Day the Earth Stood Still.

As horrific as World War II was, the new science and technology that brought it to an abrupt end was terrifying in its own right. The dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki initiated an age of mounting anxiety and fear. By the time Robert Wise began shooting on April 9, 1951, the Soviet Union had tested its own atomic bomb and President Truman had announced a crash program to develop the hydrogen bomb (which was tested by the U.S. in November 1952 and the U.S.S.R. in August of the following year). The first nuclear armed rocket, the MGR-1 Honest John, was also deployed by the U.S. in 1953. The push to develop weapons of mass destruction was hugely intensified by the perception that the U.S. and its allies needed to protect themselves from not only the Soviets, but from the communist ideology itself.

Like the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, The Day the Earth Stood Still depicts a flashpoint of fantastically increased tension and danger against a background of continuous geopolitical paranoia and increasing armament. The modality of science fiction, however, provides interesting advantages. We see our own world and society through Klaatu’s eyes. The issues that fill the news cycle from day to day - the diplomatic squabbles and ideological conflicts - are, from his perspective, simply so much noise. Not only do our governments seem immobilized by fear and mistrust, unable to recognize common sense or perceive genuine threat, but we see people very much like ourselves and our neighbors failing on an individual level, succumbing to media driven hysteria or schemes to advance individual interests no matter the cost to others. To an extent, we find ourselves slipping into Klaatu’s shoes and judging ourselves from an elevated, more rational plane.

The acting is, almost without exception, first rate, and supported by an outstanding screenplay. Beyond their superb performances in this movie, most of them also distinguish themselves in what they went on to do in the future. Michael Rennie’s Klaatu is exceedingly dignified and wise, yet also possessed of a wonderful kindness and good humor. Rennie’s stately performance, however, is almost completely eclipsed by Patricia Neal, who plays Helen Benson. Helen’s character has an unusual depth and complexity for the genre and the time. Widowed during the war, she finds herself juggling work, parenting and an eager suitor. The fact that she and her young son are living in a boarding house speaks to the difficulty of her situation, and the lives of tens of thousands of women who were in the same circumstances following World War II. We see Helen navigate her roles with admirable confidence, caution, and sensitivity. Seeing Neal in this part makes me want to see much more of her work, and it comes as hardly a surprise to learn that she received both an Oscar and an Oscar nomination in the years to come. I was surprised, however, to discover that she is also a doppelgänger of Star Trek: Voyager’s Kate Mulgrew - appearance, voice, bearing - it’s all there, and it’s beautiful!

Hugh Marlowe, who plays Helen’s love interest Tom Stevens, never won an Oscar. It is arguable, however, that his starring in 1,907 episodes of the American soap opera Another World was a more singular accomplishment. Marlowe may have had the most difficult role in the film because he had to walk the razor’s edge of being a nice enough and worthy enough boyfriend for Helen while also being slightly, then worryingly, and finally alarmingly unlikable. It’s one of those roles that is so convincingly played you run the risk of hating the actor just because you hate the character.

Billy Gray, as Bobby Benson, is as polite and precocious a child as one could hope to see on screen, and approaches being a trope for just this reason. The character is charming, and the dialogue, ranging from funny to cleverly ironic, is delivered well, but there’s something about children in older movies that is altogether too earnest.

As compelling as Edmund North’s dialogue and characterizations are, regarding Klaatu’s mission there is one gaping crack in the plot. We learn that Klaatu is a representative of an interstellar union of alien races that have come to a unique collective security agreement. They seem organized enough to have a very specific protocol, reminiscent of Star Trek’s Prime Directive, as to how and when to approach non-members. Before first contact with Earth, for example, they spend years monitoring radio broadcasts to learn the language and, one assumes, all manner of information about the planet and its people. Klaatu’s mission is to deliver a message to representatives from all the nations of the Earth, and that his message “concerns the existence of every last creature on Earth.” Klaatu suggests a meeting with the United Nations or chiefs of state, but all his efforts working through official channels are rebuffed.

The strange thing is that after having spent these years monitoring radio signals, and after Gort and Klaatu’s five-month journey, they seem to be in an awful hurry to reach an arrangement with the governments of Earth. Klaatu gives up his negotiations far too quickly. He only speaks directly with one representative from a single government before he begins talking about his dwindling patience and disastrous consequences. In a situation where time is surely on the aliens’ side, he starts making statements about leveling cities with a surprising and worrying level of haste. Lucky for us, I guess, that he goes a little Captain Kirk, throws the script aside, and decides to meet with the common folk.

Thankfully this inconsistency in the plot, the seeds of which are planted during the conversations with Secretary Harley and Professor Barnhardt, only fully crystallize in one’s mind after Klaatu’s full (and beautifully crafted) message to the people of Earth at the end of the movie. Information is dealt out sparingly, and it’s best that this is so. Not only does it make the ramp up in tension throughout the film that much more dramatic, but Klaatu’s tour of American culture and human existence is much more enjoyable if we aren’t repeatedly reminded of the fact that he might be about to order the destruction of the planet.

Barnhardt: Tell me, Hilda. Does all this frighten you? Does it make you feel insecure?

Hilda: Yes, sir. It certainly does.

Barnhardt: That’s good, Hilda. I’m glad.

One crucial thing that North gets right is that he doesn’t set up a love story between Klaatu and Helen. Whether in 1951 or today this would probably have been the expected thing to do, but it would have been an unforgivable derailment of the story. At several junctures Helen is, quite reasonably, forced to measure Tom against Klaatu, and it’s her beau that is found wanting. Tom is more than happy to pawn Bobby off on Klaatu rather than take him on their date, and Klaatu is very clear about how much he enjoys spending time with Bobby. Helen, for her part, is paying close attention. Thankfully, however, there are no explicit intimations of romantic interest, and their relationship is kept on a platonic level.

Cinematically, The Day the Earth Stood Still is a stunning accomplishment. Director Robert Wise went on to four Oscar wins for West Side Story (1962) and The Sound of Music (1966) as well as two nominations for I Want to Live! (1959) and Sand Pebbles (1967), but more pertinent, perhaps, is the fact that he came into this film with an Oscar nomination for Citizen Kane (1942). Director of Photography Leo Tover also came in with his own nominations for Hold Back the Dawn (1941) and The Heiress (1950). Editor William Reynolds also created a stunning list of accomplishments over the years, winning Oscars for The Sound of Music (1966), The Sting (1974) and nominations for Fanny (1962), The Sand Pebbles (1967), Hello Dolly! (1970), The Godfather (1973) and Turning Point (1978). The degree of skill evident in this film is nothing short of jaw-dropping. Case in point is Klaatu’s first appearance in the boarding house. Mrs. Crockett’s tenants are already on edge as they watch the latest news reports of the escape of the spaceman from the military hospital, but the sudden sight of “Mr. Carpenter” standing in the entrance to the living room, and its seamless dovetailing with the report from the newscast, is terrifying. The beautiful transition that then takes place from fear to calm is a masterclass of the use of light, shadow and camera angles. This sublime fluctuation between tension and release, the alien and the everyday, is continued throughout the film.

Movie soundtracks are like restaurants - we remember horrible meals but if a meal is “fine” it quickly fades from memory. Unlike great food, however, it’s relatively rare for me to notice exceptionally good music while I’m watching a movie. I remember being struck by the music in Joker, and the Chernobyl mini-series, but most of the time I’m left nonplussed when a reviewer praises a musical score because I can’t remember if the movie even had music. I was prompted to pay closer attention to the score in The Day the Earth Stood Still from the very first second, however, by the unintentionally hilarious, old-timey combination of theremin music and the opening credits, with their hand-drawn 3-D lettering on starry backgrounds. As the movie began, however, I found myself impressed with how the undeniably spooky theremin tones were balanced with a more standard orchestral score. The fact that it all blended so well speaks to the chops of the incredible Bernard Hermann (one Oscar, four nominations), whose career included Citizen Kane (1942), Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest (1959), Psycho (1960), and Taxi Driver (1976).

What really grabbed me, however, and told me I wasn’t watching some generic space adventure from the past, was the sound design of the spaceship’s approach and landing. It would have been de rigueur to use the theremin itself to supply the sound of the ship, but instead we are given a beautifully complex sound, a hum that’s recognizable yet impossible to place, paired with the sound of air passing quickly over metal surfaces. A deepening drone appears as it slows to land. Vibrations, a resonant buzz. Truly a masterpiece of sound effects that’s reminiscent of the loving care of Ben Burtt’s work in Star Wars.

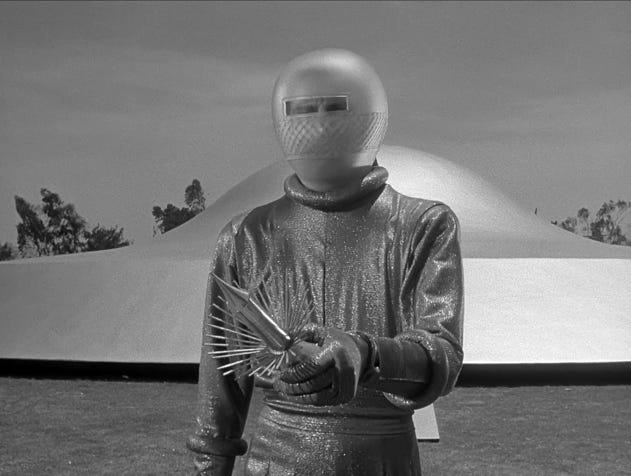

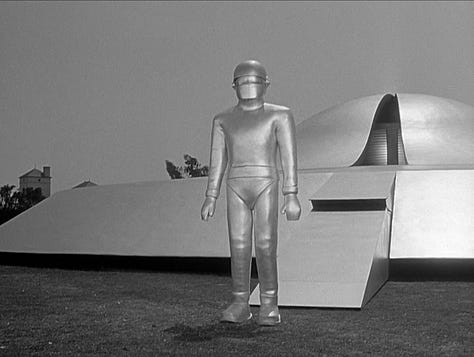

The craft itself is beautiful to behold. A classic saucer, smaller than you’d expect, with impossibly clean lines. The extension of the ramp and the opening of the upper dome was geekishly satisfying and a triumph of elegant design. When Klaatu emerges and activates the device he carries we find ourselves not just empathizing with, but immediately inhabiting the body of the terrified soldier who fires his gun. The subsequent appearance of Gort and his overwhelming but still restrained response to the attack on Klaatu amplifies both the sense of shock and the urge to flee. This is simply incredible film making.

Okay, so Gort is great/not-great - but because this is 1951, he’s utterly great. The costume designer had a huge conundrum, wanting to replicate in the towering robot the silent, unutterably smooth and seamless mechanisms of the ship itself. But, elbows and knees, right? It wouldn’t be until 40 years later in Terminator 2 that filmmakers would use digital technology to produce the appearance of liquid metal, so something like spray-painted neoprene was the closest they could get. And yes, the foam rubber tubes on Gort’s arms and legs have an unavoidable and awkward buckle. Yet, they did what they could, even going to the lengths of producing two suits so they could make it look like the suit has no seams. A fiberglass version was also made for close-up shots of the visor.

It’s striking how judicious the film is in terms of amount and quality of special effects. The budget seems on the lean side at $995 million - about the same as House of Wax and half that of War of the Worlds. They were undoubtedly lucky in that they were able to gather cast and crew who, although they were experienced, still had clocks on their mantles instead of Oscars. Luck was also on their side script-wise - the film doesn’t actually require an abundance of special effects, so they were able to make the effects they did have top-notch.

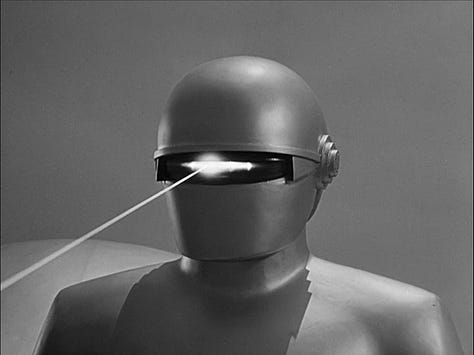

Gort’s beam weapon is especially well done. His visor rises, revealing a spooky, pulsating Cylon-like eye. The action of the beam itself is animated, reminding me of the weapons from Forbidden Planet (1956) which were rendered by Disney Studios in delicious color. Once again we see real thought being put into the effect, which proceed in stages. The light extends, fills the object to be disintegrated, and the object disappears. In the case of larger objects, like tanks, we beam retreats to reveal some kind of slag left behind on the ground.

What really stands out for me is that, ultimately, they didn’t have to do all of this. All kinds of corners could have been cut and no one would have noticed. Surely no one expected more from a science fiction movie of this era. But like Forbidden Planet you see the very successful result of a group of people working together to push back the boundaries of the technology and the genre, not just visually and in terms of story, but, perhaps above all, with reference to message. These aren’t just people who care about what you are seeing, they care about what you are thinking. After The Day the Earth Stood Still the bar was significantly and irrevocably raised. We could still be distracted and even enthralled by space operas and tales of high adventure, but never again could those movies outstrip the kind of science fiction that truly engaged our intellect and entreated us to be better than we are.